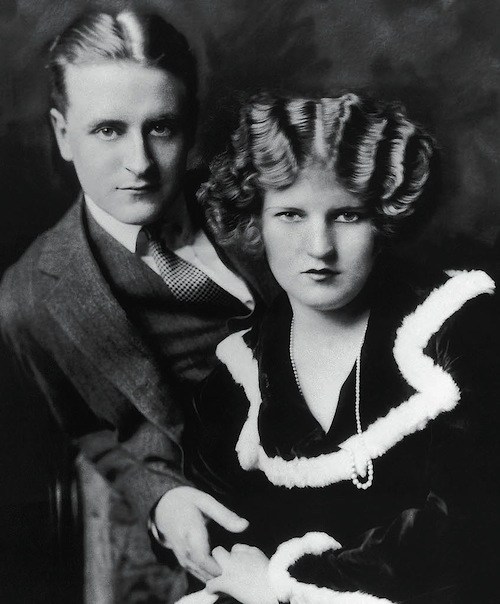

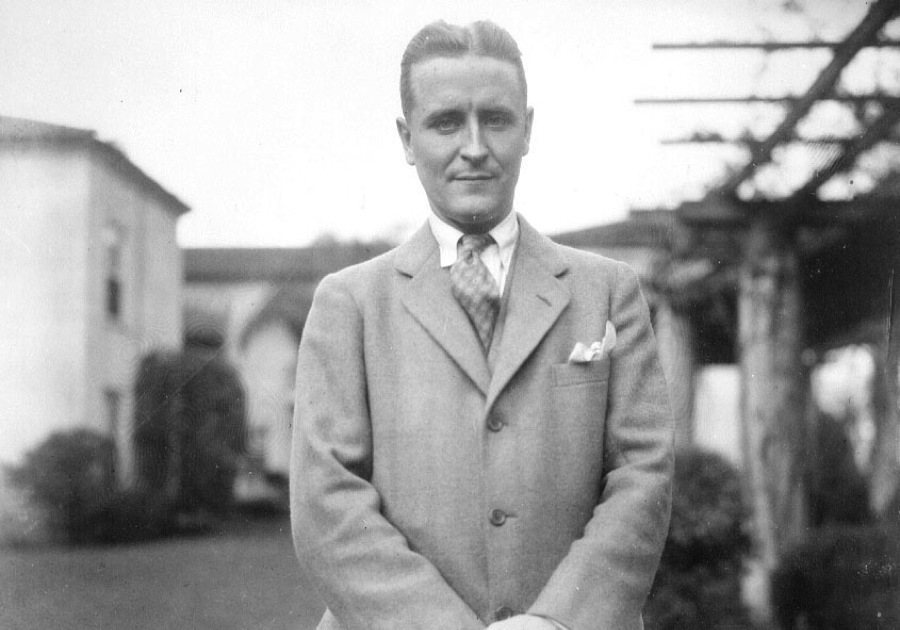

- F. Scott Fitzgerald and John Lennon - July 1, 2020

- The Artist as a Dissipated Man: Fred Seaman’s “The Last Days of John Lennon” - February 15, 2020

- John Lennon, Alma Cogan, and the Delicate Mechanism of Efficient Beatles Operations - December 21, 2019

I’ve been on something of a Jazz Age kick recently, and you can’t be on one of those without running into my second-favorite American author of all time, F. Scott Fitzgerald. Somehow the thought occurred to me: F. Scott Fitzgerald and John Lennon have a lot in common.

Fitzgerald said that all his works were imprinted with what he called his “stamp”; he said this stamp was “taking things hard.” Specifically, Fitzgerald was referring to Ginerva King, a Chicago heiress and socialite whom Fitzgerald courted in his late teens and who rejected him for someone wealthier and more socially prominent. Fitzgerald was devastated and seems to have experienced the rejection as a trauma. Sound familiar to Gatsby readers? Fitzgerald drew upon this rejection—the deep longing to be let into the world of someone wealthy, and the disjunction between intense idealization of a love object and reality—in all his works, including the scores of short stories he churned out through the 1920s, which made him one of the most famous and successful young writers of the age.

John had his “stamp,” too. We all know John’s childhood, of course, and how parental abandonment, death, and a Dickensian aunt who was ill-suited to raise a particularly sensitive boy with a family history of mental illness combusted with his innate talent to give us JOHN LENNON. I’m quite sure that those events didn’t just inspire John’s later, confessional songs like “Julia” or all of Plastic Ono Band. Just like Fitzgerald writing is going to sooner or later return to money, class, idealized love, and the wispiness of dreams, John’s early and mid-period Beatles songs are filled with a set of recurring themes: reuniting (It Won’t Be Long; When I Get Home; A Hard Day’s Night), unconditional emotional availability (Anytime At All; All I Gotta Do), a singer telling a girl that he’ll treat her right—in contrast to another guy, who’s treating her poorly (This Boy; You’re Gonna Lose That Girl), betrayal (Not A Second Time; I’ll Be Back; No Reply; I’m A Loser; Baby’s In Black; I Don’t Want to Spoil the Party). All of these can be traced back to Julia Lennon, either as wish fulfillment (all of those songs about reuniting and being there “whenever you call”) or expressions of profound insecurity caused by maternal abandonment (lack of a stable sense of self, wildly vacillating self-confidence, an Oedpial desire to save Julia from wife-beating Bobby Dykins, etc.).

Both men were able to spin these early hurts into gold, almost mechanistically at first. John spoke of having a “formula” he used to write early Beatles songs. He never said what the formula was, but I think it involved matching his genius for pop hooks to words that translated his deepest wounds into simple, relatable expressions of love and longing. Fitzgerald basically did the same thing, except his genius was for lyrical prose, not music. Like John, Fitzgerald admitted that he deliberately structured his short stories to be marketable by changing parts of them after he’d written them—i.e., hewing them to a formula. Both men arrived on their respective cultural scenes already able to do this extremely well, and then got much better at it in an extremely short period of time. Soon, they were blending craft and art, “formula” and emotion, so well that they were making Great Art: Gatsby and Rubber Soul both mark a crystallization of these abilities.

After that, a decline begins. In Fitzgerald’s case, alcohol, possible mental illness, and a codependent, mentally unstable, and controlling partner who was Bad For Him are the culprits. In John’s case, you can substitute “heroin and LSD” for “alcohol.” Both of them were so closely linked to the decades they helped chronicle and shape that they were adrift, almost irrelevant, in the decades that came next. Both of them looked to be poised for a late-career second act but died, in terrible physical health (John’s assassination notwithstanding), in their early forties before that second act could happen.

I’m most interested in why Fitzgerald and Lennon lost the plot so quickly after their early career peaks. I think addiction has a lot to do with it. As Michael Gerber observed elsewhere on this site, genius is a delicate mechanism; when you start jackhammering it with chemicals that change your brain chemistry, you might ruin it very quickly. Distractions caused by unhealthy relationships took a big toll in both cases. Both artists were involved with partners who seemed competitive with, rather than unequivocally supportive of, their genius, and whose own addictions and mental health struggles made it very difficult for Fitzgerald/Lennon to get healthy and focused in the way they needed to do to create.

But I think there’s more to it than that. Both men relied on easy access to reservoirs of personal pain. And in both cases, it was a sort of adolescent pain, and an adolescent relationship to that pain. (In Fitzgerald’s case, that’s more obvious, but John retained a very particular “my mother died, so fuck the world I’m going to get trashed” type of anger for the rest of his life.) They took a craftsmanlike approach to their work whether they realized it or not, though neither viewed their best work as craft. But to me, both men depended on the fire from those emotions to fuel inspiration for their work, “product” or otherwise. As the years separating them from those traumas accumulated, it’s possible the pain dulled. It’s possible they ran out of new things to say about it. It’s possible that their reliance on intoxicants prevented growing beyond that pain, or finding new ways to look at it, or talk about it.

Whatever it was, in both cases, it’s remarkable that they gave us so much, so young, and sad to hear the Bermuda Demos or read the first third of The Last Tycoon. There may be second acts in American lives, contrary to what Fitzgerald said, but not in the lives of those who crashed into earth like comets as very young, very talented, very vulnerable artists.

This makes a lot of sense to me, Michael B. I’d add that one of the important things that Fitzgerald and Lennon had in common was a longing for the ideal, and a restless inability to be fully satisfied with the actual. This gave a sense of urgency and a profound emotional charge to their best work, but it also made it difficult for them to lead well-balanced lives.

.

And as you say, both men were perpetually revisiting their earlier life. Fitzgerald’s line at the end of Gatsby that “we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past” seems to me to apply to Lennon as well. And it’s not surprising: early traumatic experiences will do that to you, especially when no good therapy is available to help you process what happened.

.

They have similarities in writing style as well. Both constructed lines of great compression and lyricism that are breathtakingly beautiful and that also bear their distinctive “stamps.”

@Nancy, “One of the important things that Fitzgerald and Lennon had in common was a longing for the ideal, and a restless inability to be fully satisfied with the actual” — I love this. I think it also contributes to what I was trying to explain, why they struggled as they aged out of their twenties and into their thirties. The dream probably seemed so close they could scarcely feel to grasp it as 24, 25, 26 year olds, and the frustration at not being able to do so (and maybe, even, not being able to write the same way they could when it was less elusive) was probably heartbreaking.

.

Great point about their writing styles, too. (Also, *musically,* Brian Wilson strikes me as the most Fitzgeraldian of the Sixties songwriters.)

Love this as well as the Dickens comp for Paul. In a 1986 interview I posted here recently, Paul calls John and Yoko “Scott and Zelda”, albeit sardonically. I’ve seen a Hemingway comp in an article about John once, although that may have been related more to the two men’s personas than their writing styles.

A weird coincidence:

A few months ago I started reading Fitzgerald. I had only been acquainted with him from reading The Great Gatsby in high school, as well as gossip about him in biographies of his contemporaries.

I remember 45 years ago reading James Thurber, and in his essay “The Incomparable Mr. Benchley” he claimed Benchley understood Scott better than anyone, when the moon was up and the jugs were uncorked (or whatever euphemism Thurber used for alcoholism) and I’d read lots of Edmund (Bunny) Wilson. So until a few months ago, I’d read more about Scott than his own writing.

Anyway. I’ve spent the past few months reading Fitzgerald. Everything from the Pat Hobby stories to the novels. A few weeks ago I finished “The Crack-Up” and I actually bookmarked a quote, because it reminded me of Lennon spending his final years sitting and staring into space in the Dakota. I had intended to leave it in one of the HeyDullBlog threads, but couldn’t decided where, and then forgot about it.

Here’s the quote:

The combination of a desire for glory and an inability to endure the monotony it entails puts many people in the asylum. Glory comes from the unchanging din-din-din of one supreme gift.

That’s a very apposite quote, Sam. I’d also add, to the larger comparison of Lennon to Fitzgerald, that both men were simultaneously fascinated by money and repelled by what people would do to get it / what it made of them.

.

Fitzgerald could paint the allure of Daisy’s voice that is “full of money,” and also reveal the criminality that Gatsby falls into in an effort to get rich. The way Daisy and Tom are willing to smash up people and things and retreat into their wealth afterwards is one of the most damnning indictments of privilege in literature. But Fitzgerald also wanted to be rich, and was vividly aware of his own ambivalence.

.

Similarly, Lennon could sincerely imagine having “no possessions” and yet keep extra apartments at the Dakota to store all his stuff.

This is very good, @Sam, thank you.

.

And the insecurity about money. Scott saw a couple like Gerald and Sara Murphy with their inextinguishable, inherited wealth and then saw his own fortune (generated from his talent) evaporate in a few short years.

I remember Scott’s essay about Ring Lardner. He felt Lardner had exhausted his creativity because he’d based it on the “boy’s game” of baseball. His advice to Ring was to find something deeply hidden and personal within himself to write about. Lardner, the old newspaperman and sports writer must have looked at him like he was crazy after hearing that. But Scott’s advice reminded me of Lennon’s decision to bare his soul in both his music and interviews.

@Michelle, that’s a great quote. (For reference, it’s “Yoko met me before she met John. You won’t hear that from them, ‘cause they’re Scott & Zelda. They want the story just how they put it out.”) I barely see the Hemingway parallels with Lennon, except to the extent that the pre-fame Lennon was an alcoholic with a tough veneer masking a more complicated and fluid sexuality.

@Nancy and @Sam, great points about Fitzgerald/Lennon and money. I’d add that this ambivalence also manifested in both men possibly unconsciously wasting away their fortunes.

Yeah, I was surprised by the comparison and couldn’t help but think of Bungalow Bill. I don’t see many similarities either other than Hemingway was a man’s man, suffered from depression and was cat crazy. Fitzgerald is more apt, I think.

Nancy, your Tom and Daisy reference really struck me. Someone who was in John and Yoko’s life in the late 70’s used that exact quote to describe the two of them. I read a number of books about that period in their life in a very short time so I can’t recall who used the quote (Fred Seaman seems most likely, but I can’t say for sure). It hit me as so truthful that I marked the page in my copy of Gatsby. “…they retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made…”

Great article. Thank you, @Michael. There is, also, the peculiar tragedy of being just the artist the culture wants (needs?) during a certain handful of years, being swooped up to Olympian heights and then…where to go? Decades of life must be lived, and yet…

.

You believe you are the worker, but actually you are the worked-upon. This process is always heartless, but the psychological damage seems to be particularly savage when it happens before 25. It takes WILL to die of booze at 44.

.

This deadly nature is ironic given that *youthful* success in the arts is not only the most sought after kind, it’s rapidly becoming the only type on offer. Fitzgerald and his 1920s created that paradigm for the literary world; now there are few truly successful debuts over 30. Lennon and his 1960s set it for music and art. In the 80s and 90s it was imported to tech.

Yet people line up to leap into the volcano. Here’s maybe a clue why. This, from Fitzgerald’s Wikipedia page, “In the 1950s, [the critic Edmund] Wilson, who had attended Princeton with Fitzgerald, noted that Fitzgerald had taken on “the aspect of a martyr, a sacrificial victim, a semi-divine personage.”

“You believe you are the worker, but actually you are the worked-upon.” Michael, I think you capture something important about what happened to Lennon, in particular.

This has nothing to do with Lennon, but I have a question for Michael Bleicher:

What did you think of Baz Luhrmann’s 2013 adaptation of The Great Gatsby?

I’ve never seen the whole thing on a big screen (the way I suspect it should be experienced), just various scenes on youtube. How do you think Fitzgerald would have reacted?

I sort of have a fantasy of going back in time to 1935 and arranging a screening with Scott and Thalberg, just to get their reaction. (My thoughts during pandemic lockdown often travel down odd highways.)

I understand Scott’s granddaughter liked the film. Would Scott have been thrilled or offended by this adaptation? Any thoughts?

@Michael G.: that Wilson quote made me think “John Lennon after 1968.” Both Lennon and Fitzgerald seem to have been acutely aware of the fact they had decades left during which they would never be as relevant as they had been at 25, and they both seem to have been unequipped or unwilling to take that step back from the road to Olympus. Bob Dylan was in almost the same position as John Lennon in 1966, but he seems to have said, “to hell with that” and, whatever his ups and downs since then, been content to never be that great again. The same thing that made John Lennon *more* famous, *more* idolized than Dylan in 1966 was what made him unable to take that step back, no matter how much he wanted to.

I don’t think Lennon wanted to step back, though, and I don’t think Fitzgerald did, either. I don’t think “normal life” interested either of them — which is why they paired with the women they did.

I agree. I think they only wanted—or were instinctively wired—to do one thing, which was to rush up and toward the volcano.